“Just like the old days, eh? Except it’s no longer the mini-mart. Yes?”

“I can open the vault!” - dialogue from Roger Avary’s Killing Zoe

At sixteen, I pulled off an armed robbery with three other kids. I supplied the gun, which was mine. A chrome 9mm Beretta, a literal gift from a surreal and broken home life that had already crested and was now hitting a deeper downturn that I felt, at the time, couldn’t get any worse. It was the mid-nineties. I also suffered like many others from that teen boredom that hovered like fog over the monotony of my inconsistent Westside public High School attendance. We ripped off a small-time drug dealer from another school for prescription pills, a sandwich baggie of psychedelics, and a couple of eighths of mediocre pot. The oldest kid, the 17-year-old mastermind I called a friend, drove the getaway hand-me-down Montero. I met the others, two pimply dressed down Valley elitist heshers, that day, and the whole dynamic seemed to devolve quickly.

I began to find some much-needed clarity in the car ride away from the scene of the crime, which had gone off okay but was now unglueing itself more rapidly through the paranoia of the two strangers. I could sense something was off that I can only describe as that uneasy feeling you feel when watching The River’s Edge.

In the end, I made it home to the sad sixties Westside apartment I lived at with my father, put the gun back in its place, and waited for one or all of them to sell me out or someone to get busted…..then sell me out. I, after all, had more to lose than the others.

With a few moves, I unfolded my futon, which converted from a couch to a bed, and laid down. Then, I waited a while to get arrested.

Then I waited some more.

It didn’t happen.

Over the next few months, I distanced myself, spent time writing while smoking cigarettes alone at a Ships diner, and concentrated on teaching myself filmmaking on the Super 8mm I found while cleaning out my grandmother’s garage. I wanted to and was getting lost in the idea of contributing in some way to the world of independent cinema, which, at this point, had caught my attention. For most, watching movies can offer escapism; for me, it seemed like a way to escape a bad situation without selling out.

Eventually, that memory of my armed robbery locked itself away tightly somewhere in that child’s coin Fort Knox safe that lives in the back of my brain. It rested there for three decades until it was broken out recently, in the way an Eastern philosophy old-world medicine man can see what’s wrong with your liver by putting two fingers on that pressure point on the side of your left arm. My fall from grace? Not really. Although I didn’t fully understand it then, that train had been picking up steam for a few years. And I was guilty of more yet somehow avoided capture between 13 and 16, testing the boundaries of the edgy world I felt forced to be a part of. Depending on how you might think about this type of behavior comes about, I think it’s a fucking miracle I wasn't worse. My father, let’s say, spent his life operating wildly outside the law. I would call him a career criminal. My mother’s second husband and half-sister's father was a gangster in the Scorsese sense. And both did time in serious prisons. My uncle was a little different in that he went into The Federal Witness Protection Program after getting busted for drug smuggling in the seventies and was never seen or heard from again.

So yeah. It’s all there. It’s a part of who I am. A part of where I come from.

I thought a little more about that old futon in my small bedroom, which conjured more fragmented images of the era, like a low-end version of basic cable’s Home Shopping Network with these two guys yelling as they sold viewers cheap collectible swords, Beanie Babies, and bundles of pocket knives on clearance that I would watch in disbelief during downtime. I also thought about how much I hated Pearl Jam and hippies then—that half-filled-out Slamdance application on my old desk. I thought about those weird Planet Hollywood jackets with the puffy leather sleeves you’d see. I thought about hanging out with Morgan in her room in a shabby house in Laurel Canyon when her mom was at work. I thought about functioning on little to no sleep while moonlighting as a script reader and being put under unrealistic deadlines by mid-tier film execs. I thought about Parliament Lights, Tower Records, the fake I.D. in my wallet, my mom’s blue Miata, and empty Arizona Iced Tea cans lodged in the passenger seat door storage with her sun tan lotion.

I also thought about Roger Avary’s standout directorial debut, Killing Zoe. It was a major film in my development that had, at some point later, also disappeared into that safe in the back of my head. I think now it makes sense why it struck a chord.

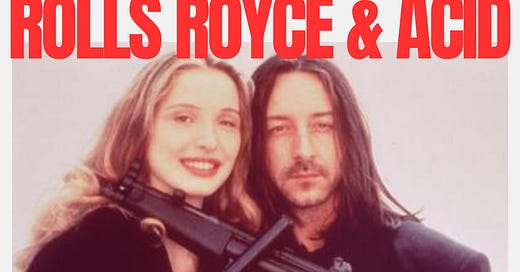

Roger Avary may be best known as the co-writer of Pulp Fiction, who, alongside Tarantino, took home the Academy Award for Best Screenplay in 1994, proving that two former video store clerks with good taste, an ear for dialogue, and a New Hollywood sensibility could land a solid punch against the jawline of industry powerhouses and their Kevin Costner sweeping epics. Killing Zoe would make itself known around the same time, executive produced by Tarantino and starring Eric Stoltz as Zed, in what I think is Stoltz’s finest hour, as the laid-back and dependable American safe cracker who touches down in Paris to pull off a bank robbery with his charismatic yet deeply unreliable and psychotically obsessive junkie childhood friend in a layered performance played expertly by Betty Blue veteran Jean-Hugues Anglade. The title character of Zoe, the call girl sent to Stoltz who coincidently works days at the bank he robs with Anglade’s Kelly’s Heroes by way of Performance crew, is powerfully helmed by Julie Delpy, would introduce her acting to me and many other misfits who hung around the art houses. She’s also the film’s heroine when push comes to shove.

Zoe - “I am NOT a prostitute!”

Zed - “That's great. Can I have my 1000 francs back, then?”

While the 1990s spawned many a shitty gangster indie trying to capitalize on the partnership and scene Avary helped found, his film is unto itself both in tone and execution. Nailing that jet lag haze you get when stumbling off your international flight as you try to adjust to that off-grey Euro daylight and that long, lonely, windowless stroll down an impersonal hotel corridor before being jarred into hanging out with friends and new strange acquaintances before you’ve had a chance to adjust to the time zone in a way that would make Melville sign off on Avary’s sly and highly realistic feeling setup.

We watch Stoltz keep up the pace as he’s thrown from a night’s bender into the heist, nursing a hangover of cheap Spanish wine, heroin smoking, and other unknown substances. Well….he’s a professional, but it all falls apart extremely quickly while he is down in the basement tending to the vault solo, thanks to the others.

Perhaps the most impressive technical aspect of the film is something I learned from Avary himself when he spoke at the film school I attended around 2000, which, unbeknownst to me, Avary had also attended. The cramped hotel hallway I mentioned, the unmistakably French apartment with the high ceilings and those slim door handles belonging to Anglade, a basement Jazz club, and the dignified bank decorated for Bastille Day, where most of the film is set, were all filmed in L.A.- about 98%, to be exact, with the exception being a day in Paris with a camera mounted on the hood of a car. As a kid, I spent time in Paris, wandering around away from the tourist traps, and I felt I genuinely knew the feel. I considered myself savvy and never once questioned it. As a young adult, I also wandered the streets of downtown Los Angeles making my student films, never thinking something like that could be done so seamlessly or even possibly pulled off believably in one of the many shuttered buildings off Skid Row.

I remember cornering Avary afterward with a friend and asking what he thought was the best path forward. He looked me square in the eye and told me to drop out of film school and find the money to make my own feature film—sage advice in hindsight.

Thank you, Roger, for Killing Zoe.

The real McCoy.