On that day, I was wearing Mannix’s suit.

First, you should know I’m not in the movie or TV memorabilia trap of collecting objects. I’ve always felt this type of historic preservation should be in the hands of the white-gloved stewards of legacy with long rectangular climate-controlled rooms, donors, roving docents, and an excess of additional square footage that can be utilized when needed. Or, on the flip side of that coin, I like the idea of some screen-used item unknowingly being sent into the void due to a movie studio lackey’s clerical error, resulting in the much-coveted thing being reborn into a new life of practicality and anonymity.

That one space chair you remember from that one shitty science fiction franchise you hate could be living the quiet life in the waiting room of a Pico Rivera muffler shop. Complimentary drip coffee and a seat in the captain’s chair for any unassuming regular Joe or Jane waiting on a lube job. At this very moment, perhaps something from The Treasure of the Sierra Madre is keeping a broken fan upright somewhere in the world.

Second, television detective reruns have kept my head together since I was a kid, home from school, with the chickenpox.

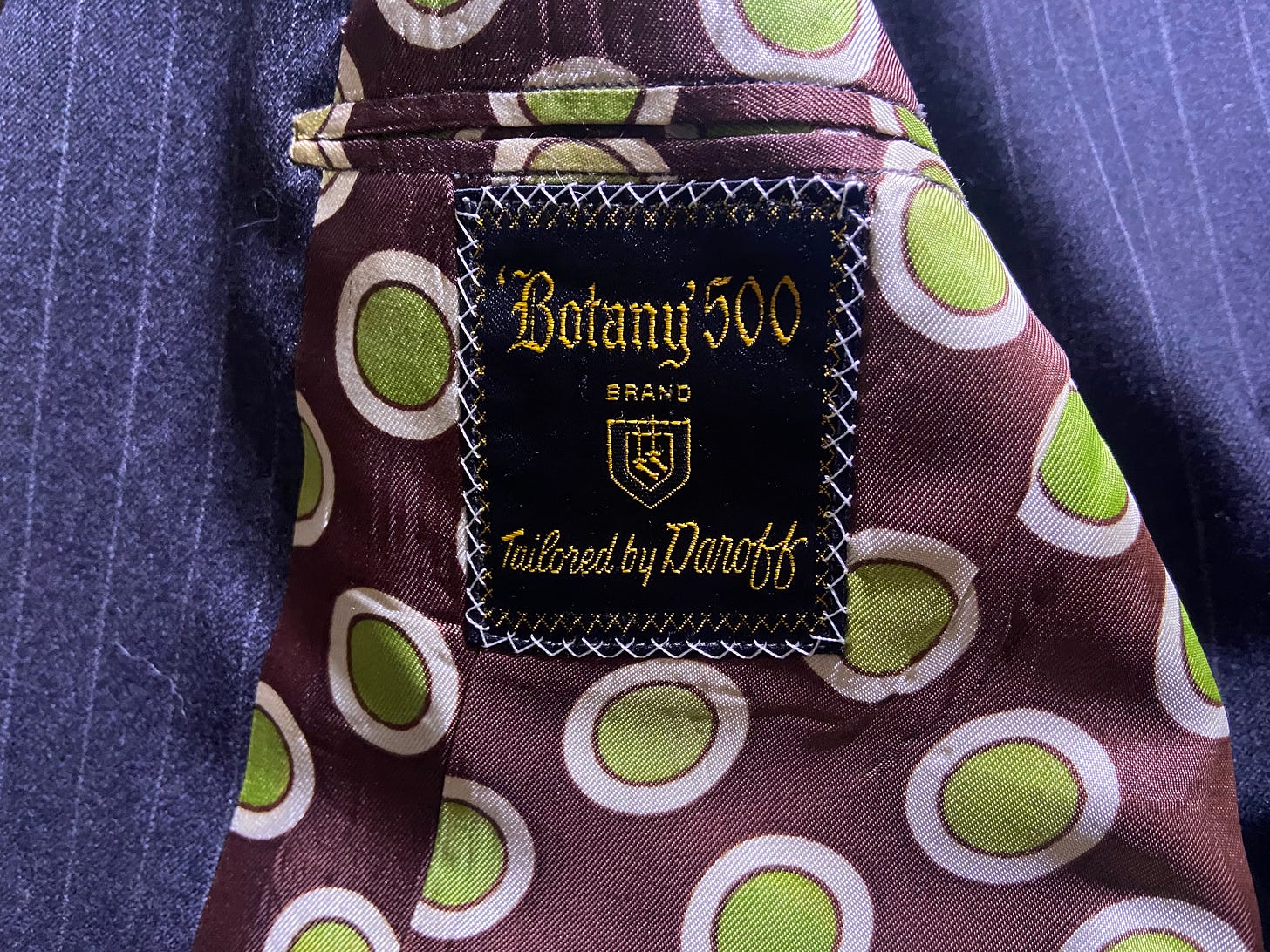

From 1967-1975, Mannix was the slick private eye played by Mike Connors in a brand new custom Botany 500 suit or sportcoat in every episode with his cool, foxy, and shrewd (more than a) secretary named Peggy. The show probably interested me because it took place in my own backyard in L.A., which was typical for most of the genre of the late sixties and seventies. Still, this detective show, in particular, had an unapologetic flash and swagger like I was used to in my own life while simultaneously examining and exposing the Angelino cracks in the Venere of it all through the Encino country club shakedown golf hustlers, Brentwood’s triangulating trophy wives’ double and triple crosses, strung out rock stars mixing it up at an alternate version of the Century City Playboy Club, Mopar 440 car chases through Griffith Park dressed as Mulholland Drive, and gangsters getting cornered and shot in abandoned cement factories off La Cienaga. Justice was always delivered in the final minutes of an episode with a mild touch of that scorched-earth cynicism that made Paul Newman’s Harper work so fucking well.

And like Mannix’s episodic guest stars, my parents had come from his era and turf with plenty of their own edginess warranting a visit from the west side super sleuth. Maybe Mannix was a window into understanding myself?

By 2006, while in my twenties, the show was still a go-to and thankfully had better time slots than when I was a kid—usually then shoehorned between The $25,000 Pyramid and Days of Our Lives. Since my initial discovery, basic cable and DVD had leveled the Mannix playing field. I could now throw it up on my sometimes working ProScan big-screen television set and watch comfortably at night with a cigarette on the couch of my hillside apartment. My girlfriend at the time was a near-permanent houseguest at Leonard Cohen’s humble Los Angeles compound/duplex off Pico, which also hosted his family, extended family sometimes, his stunning muse, and the occasional Zen monk from Mt. Baldy. My sparsely furnished shack couldn’t compete with any of that, so we spent a lot of time over there drinking great coffee out of old promotional cups for L. Cohen’s nineties album The Future. It’s tough to pick a favorite record of his; it varies for me based on what level of introspection or depression I’m dealing with at the time, but that one is in the top two album covers in my book.

The hummingbird.

The blue heart

And the open handcuffs.

I had been in such bad shape during that chapter of living. My old leather jacket smelled like I’d chain smoked 20,000 cigarettes, I had a hole in the sole of my Lucchese cowboy boot that let water in when it rained, I couldn’t afford to get the driver’s side door handle on my car fixed, the bank account felt like one hefty continuing overdraft fee, and I had serious problems getting out of bed before 4 pm.

My future was looking dim.

When I met Leonard, I didn’t know what to say, so I nervously defaulted to “Hey, man.” Which seemed, at the time, like I said the wrong thing, but he responded with, “Hey, man.” Then, he put a handful of chocolate Gelt coins in his warm handshake. It was the holidays—a Jewish custom. I kept the chocolate as a reminder of this great event. From that point forward, whenever I saw him in one of the two living rooms or passing in the front yard on the way to his SUV, it was always, “Hey, man.” back and forth as the greeting.

Unlike the way that you saw him during the eighties and nineties when his clothes looked perfectly pressed by some Grand European hotel laundry service in his music videos, those suits had now seen some life and were his daily drivers even around the house in the way that you may imagine what sitting with an old French bohemian in 1930s was like—or being taken through a hidden passage behind a bookcase by a member of the resistance during WWII. The wrinkles in the fabric, the life it lived and was now living, and not treated with a meticulous and obsessive quest for creases in dry cleaning plastic like my parents had hammered into me, making it tough to sit or eat anywhere comfortably.

This was something real—a better way to live.

I told myself then, “If I make it to middle age, that is someone to take my cues from when I get there.”

L. Cohen is gone now. So is M. Connors.

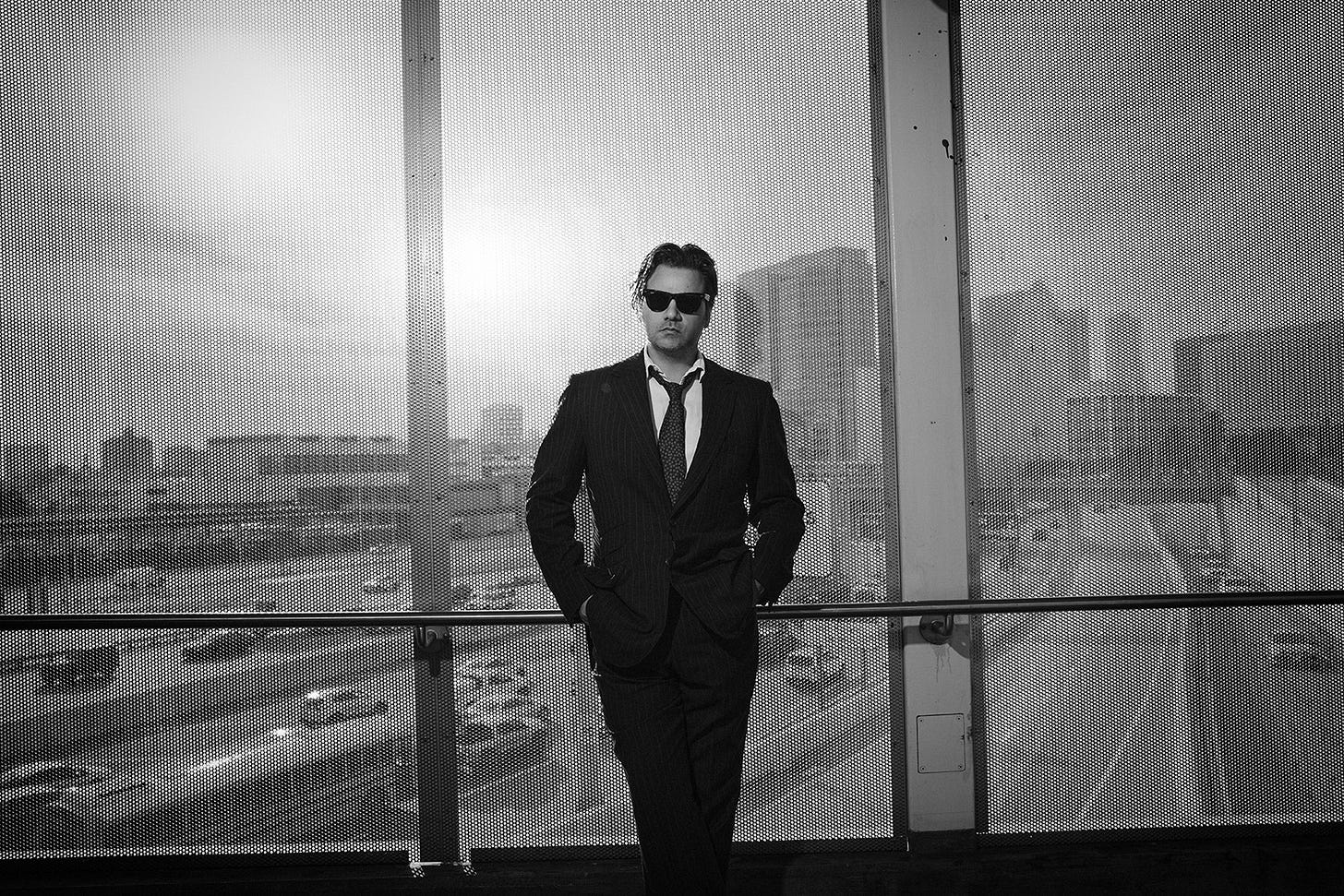

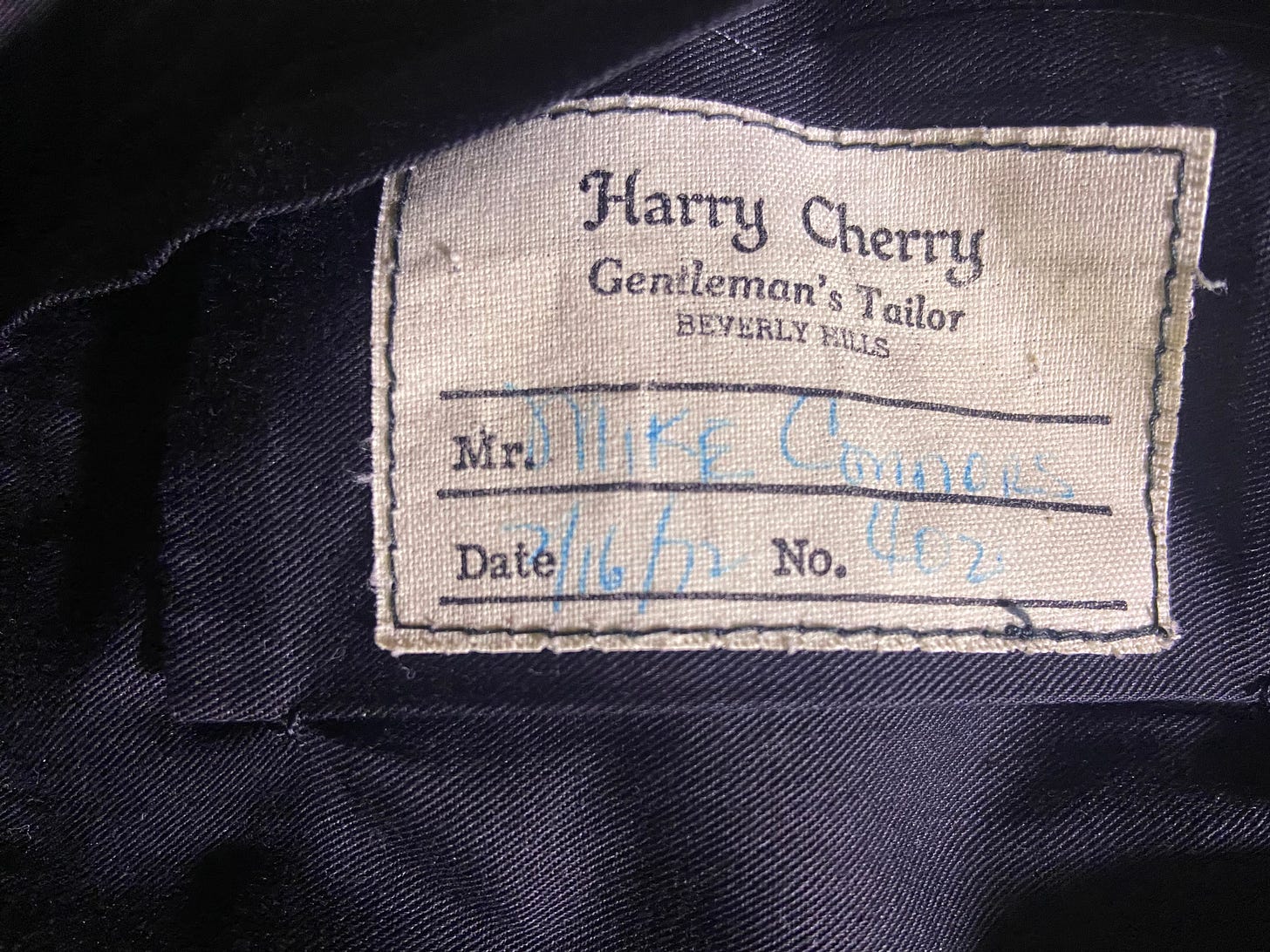

But recently, I wound up with an unwanted double-breasted dark grey pin-striped suit from Mannix procured by my girlfriend during the final minutes of the Mike Connors estate sale—twenty dollars to get it out of there, and it wound with me.

Dated 2/16/72

I tried it on, and it fits.

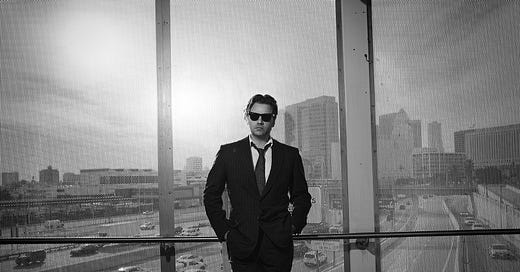

My portrait by legendary indie rock photographer Piper Ferguson.

Check out her new photo book INDIE/SEEN, published by Welden Owen.

A few references are in there to Leonard Cohen’s album The Future, and watch an episode of Mannix.