THERE IS A TIME TO DIE AND A TIME NOT TO (part two)

Walking Down the Incan Highway With Hopper's Last Movie Guide & A Club Sandwich Where Helmut Newton Checked Out

On the third and final day, I shot my ending.

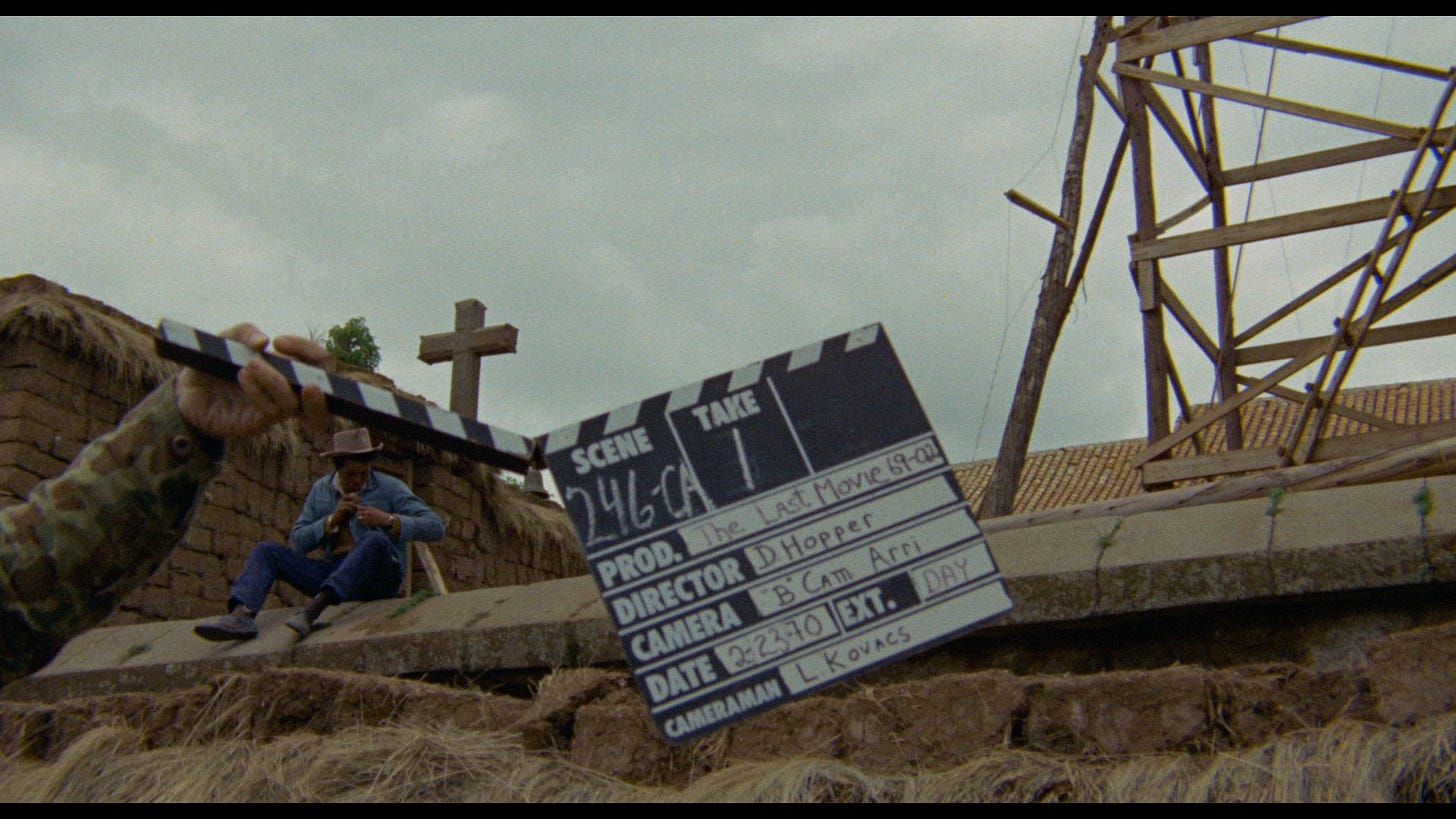

Hopper’s guide had become our guide, and my questions about Chinchero and the locations used in The Last Movie were being answered by the person who knew how to answer them better than anyone else. This man led Hopper, cinematographer Laszlo Kovacs, and producer Paul Lewis to all the places that had struck a chord with me in the mid-90s after pulling the VHS tape out of the video store on La Brea in my teens. Now, we were retracing their steps from 1970 at around 12,400 feet. I was rolling with it in the thin air and momentary altitude sickness, pushing through with our gear as Tomas, a man in his seventies, charged forward, offering us freshly picked medicinal herbs when he noticed anyone slow down. Our small crew, well under half his age, huffed and puffed up the ancient stairways sometimes while being stared at by sheep, llamas, Native shopkeepers, and the occasional German adventurer on holiday. No one wanted to disappoint Tomas by showing weakness as he charged forward. The right-hand man, Satya de la Manitou, around seventy, had ignored all the cautionary documents about work in the Andes, knocking back bottles of red wine at our dinners at the hotel in Cusco. But he had lived through the 1970s, the dark and challenging years with Hopper on Mad Dog Morgan, Tracks, and The American Friend, negotiated with drug-addled psychopaths, and evaded capture in the edgiest of situations, so who was I to stop him? Besides that, it was impossible to reason with the man about this. Watching them both operate, I started to see how The Last Movie was made. A question I had asked myself since landing in Cusco. Their generation of seekers operates from a different plane. A lost tribe of superhuman challengers, provocateurs, and risk-takers who headed into the unknown and moved all the mountains for the rest of us.

While we designed the shooting sequence, Satya channeled what he had learned on stage with Cassavetes and the tips taken from Wenders in Hamburg, and when I yelled “Action!” on our final day, we continued in tribute to the work started there by his best friend. I had found something up in the mountains—my own spiritual awakening with a movie camera. The things I faced back home in L.A. felt less and less of a headache. Maybe this energy helped channel his infamous war for his Final Cut.

Tomas and his family had also supplied us with ponchos used during the making of The Last Movie, which provided us with further method juju as the day progressed.

We filmed in the old plaza, where Hopper’s character Kansas rides in on his horse, interrupting Sam Fuller’s production starring Dean Stockwell flanked to one side by false fronts of a production-constructed wild west town named “Llama, New Mexico.” Named in homage to a commune Hopper had visited and where Satya was living in 1970. Satya had been unable to make the journey to Peru due to the birth of his son, and something in him had always slightly regretted missing out on filming what would become the most critical film project of his artistic trajectory. Fuck it, better late than never, he finally made it, and so had I.

Another buddy of Hopper’s, James Dean, also found tribute in the name of one of the storefronts. A fortune teller’s shop. It's hard to imagine all these paths, icons, and ideas converging here, facing a Sacred Mountain worshipped since the days of the Incas. Toni Basil did her thing in a makeshift saloon stage decades ago, where I’m now standing as the hail starts to fall on me.

I had expected to get more wild stories about “Denny Hooper” and the strange and crazy New Hollywood movie stars & freaks who descended on the small village at the end of the sixties. Our translator would converse back and forth with Tomas in his native Quechua. Stateside, I had been inundated for months with stories of overly plentiful cocaine highs set to the construction of Me and Bobby McGee, late-night LSD trips in pickup trucks with alien visitation, CIA infiltration of the film crew, a rumor about wanting to dynamite a historic wall for a shot, and a cash shakedown from the village Catholic priest looking to unload religious artifacts on the group of west coast gringos with deep pockets to keep his parishioners showing up for their scenes.

For the final Chinchero sequence, we were pointed in the right direction to the cliff facing the village’s Sacred Mountain, where Dennis had stood next to the bamboo camera in set photographer Peter Sorel’s haunting photos, many selected for the film’s advertising campaign—one of which we had carried through production. It became my and the film’s mission statement.

We quietly filmed the final shots almost telepathically. “Cut,” I quietly said as we finished.

I intuitively knew we were okay as we faced the Sacred Mountain surrounded by the terraced hills and village walls.

The connection between Hopper and the village was deeper for them than most people realize. Tomas expressed that he had a longstanding reverence for Dennis. They were almost the same age, and Dennis had endeared himself to Tomas and his family by telling them he was a “shepherd of cows,” alluding to his humble beginnings on the family farm in Dodge City, Kansas.

Hopper had also been trained to ride by Warner Bros in the mid-fifties and knew his way around a horse, which was impressive as horses were still a primary mode of transport in Chinchero. The natives read him and accepted him much like the tribe at Taos Pueblo had done a few years earlier during the filming of Easy Rider (a strong relationship that would last for the rest of his life). This connection to the villagers led Hopper to support the people with much-needed modern improvements, jobs on the film, and updates to the village, even sending lumber from the production to construct better roofs on their homes.

As we came down from the experience, Tomas asked us to walk with him. I was feeling our day in the Andes. There was about an hour and a half of light, and I was ready to fall down, but he insisted.

So we took a walk with him down the Incan Highway.

Our steps turned into miles as we wound deep into the mountains. Little was said between all of us as we followed. At one point, Tomas took the tripod off my shoulder and carried it himself the rest of the way. He quietly picked fresh herbs as we took the trip down the path cut into the mountain centuries ago.

And when we got to where we were going, I knew exactly where we were.

We climbed down to the waterfall. He was incredibly proud of this place, and as we watched the water cascade down, Tomas pointed and said, “This is where Dennis Hopper showed me a naked woman.”

Referenced Music - Kris Kristofferson’s Me and Bobby McGee

Photos credits - Along for the Ride, The Last Movie, Danny Reams, Cecil Beaton, and Peter Sorel.

Basil & Stockwell artworks by Me